The Deep Roots of Geopolitics II

Implications for the Future

In Part I of this post I pointed out that geopolitics today is dominated by the confrontation between “Oceania,” a result of the Gunboat Military Revolution, and Eurasian Empires, a result of an earlier Iron-Cavalry Revolution. This is fascinating history, but it also has implications for how this confrontation may evolve in the future.

The most important point has to do with remarkable endurance of Eurasian empires that originated on steppe frontiers. All large-scale societies organized as states experience recurrent end times, periods of social turbulence, political infighting, and state breakdown. But what is different about empires on steppe frontiers is they have a certain kind of resilience. After a collapse and a period of fragmentation, a successor empire seemingly inevitably reforms itself in the same region. This is quite different from the dominant pattern in regions away from steppe frontiers. Thus, after the collapse of the Roman Empire, Italy persisted in a fragmented state all the way into the nineteenth century.

This pattern has long been noticed for China and has generated quite a lot of interest from historically minded economists. As an example, take a look at an article by Fernández-Villaverde et al., The Fractured-Land Hypothesis, or read about in Walter Scheidel’s book, Escape from Rome.

The fractured land hypothesis: Why China is Unified but Europe is not

Much earlier, Luo Guanzhong begins his historical novel, The Romance of Three Kingdoms, in which he traces the turbulent century of national disunity following the end of the Han dynasty (169–280 CE) with these famous lines: “The empire, long united, must divide; long divided, must unite.” In Part I you can see the map showing how many mega-empires ruled China. There were ten! (plus 4–5 additional unifications that were partial, and didn’t exceed the mega-empire threshold of controlling more than 1 million square kilometers). But Iran did even better—12 mega-empires! Russia, as a late comer, has a shorter record, but the general pattern there was the same.

The mechanism generating recurrent imperiogenesis on steppe frontiers is the Mirror-Empires model that I proposed in a 2009 article, and extensively tested in subsequent publications. The argument goes like this. Steppe pastoralists needed the products of agrarian economies (food and fiber). They also enjoyed a military superiority over the farmers, thanks to an infinite supply of horses and the way of life that cultivated fighting prowess. They could trade with the farmers, of course, but it was much more tempting simply to rob them. After the nomads learned how to effectively ride horses, farming communities on the Steppe’s shores were constantly under severe military pressure and the only way they could resist it was by unifying into an empire. Inner Asians also created imperial confederations, and the two kinds of imperial polities scaled up as mirror empires, one on each side of the steppe frontier.

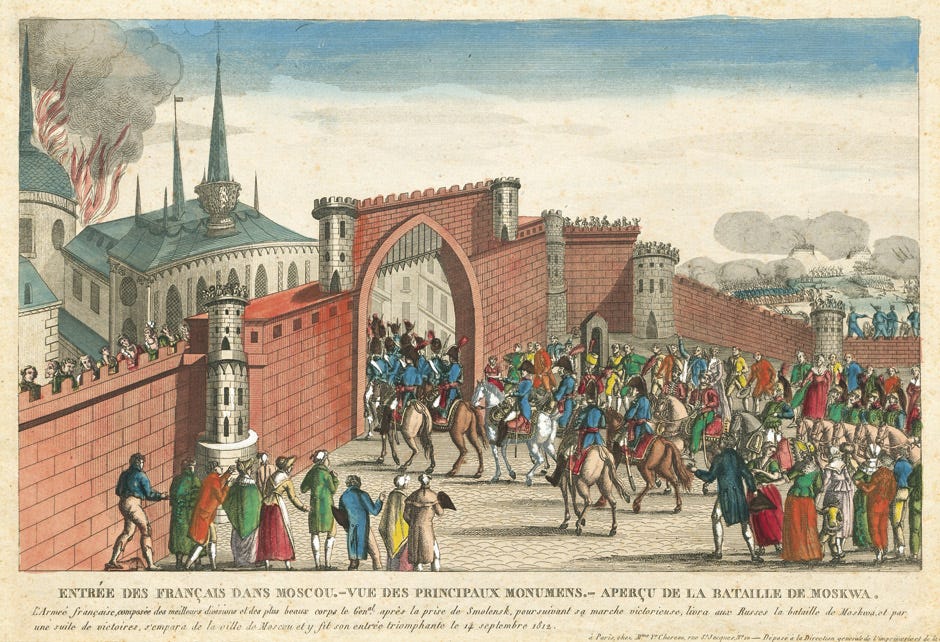

When the Europeans with their ships and guns replaced the steppe pastoralists, their effect on other polities was analogous. Russia, closest to the epicenter of the Gunboat Revolution, was first to experience the pressure from the (West) Europeans. It was, as a result never conquered (although the Poles, Swedes, French, and Germans came awfully close, with Poles and French actually occupying Kremlin).

But Russia was lucky in that it was given time to co-evolve with the Europeans, so that Russian artillery, for example, was equal to the armaments of its European rivals.

When I say “co-evolved” I primarily mean cultural and social evolution, but there was an element of biological evolution in this process. As Jared Diamond famously argued, Eurasians were exposed to repeated waves of pandemics, and had many centuries (indeed, millennia) to adapt to these pathogens.

Complex societies in the Americas, on the other hand, were not given time to adapt, and collapsed as soon as they were exposed to the European invaders. But let’s get back to Eurasia.

China, on the opposite end of the continent from Europe, felt the brunt of European expansion much later than Russia—only in the nineteenth century, when the Qing Dynasty entered its disintegrative period. But it survived the ensuing Century of Humiliation and has now regained the status of a Great Power.

Iran’s story was similar to China in that it came under European pressure late, in the nineteenth century. Actually, both Iran and China were squeezed from two sides: from maritime powers (chiefly British Empire) and from the land-based empire (Russia). Here’s a bit of history, little known in America: the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran.

OK, what’s the point of reviewing all this history? The Eurasian Empires are extremely resilient entities and tend to reconstruct themselves following state breakdown. The mechanism is external pressure, first from Inner Asia and later from Oceania. This means that the current American policy that aims to put as much pressure on China, Russia, and Iran is likely to lead to the opposite result form the one intended. All these states have evolved cultural adaptations and imperial traditions to respond to external pressures by becoming more internally cohesive. In my view, the inevitable result of the current American policy will be that the geopolitical balance will eventually shift decisively in favor of Eurasia. In other words, blowback.

So far, I’ve been looking at the current geopolitical confrontation from the Eurasia’s point of view. But what does history tell us about Oceanic powers? Unlike resilient Eurasian empires, maritime great powers tend to be relatively short-lived. World Systems theorists, such as Giovanni Arrighi, have a list of “hegemons” preceding the current one, USA. These are, in reverse chronological order, the British Empire, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Genoa (see a recent article by my colleague Chris Chase-Dunn). In my opinion, only the British Empire qualifies, while calling Genoa, Portugal, and the Netherlands “hegemons” is quite a stretch.

Still, it is an interesting set of polities to consider. Each of these states, from Britain back, enjoyed its heyday and then declined into insignificance. There could be many explanations for such impermanence, but one is that they all were, or soon became, plutocracies (the rule by the wealthy) and plutocracies tend to be quite fragile, for reasons that I explain in Chapter 6 of End Times. If America fits this pattern, its days as a hegemon are numbered.

You see, when the West applies pressure, it expects fracture.

But pressure, in the Eurasian core, becomes myth,

and myth becomes state again.

How would technology possibly change this? Previously empires and power blocks had hard currency (gold, silver etc), whereas now much of this is digitised/tokenized and centralised. The western dominance of global finance is also unprecedented (?) in its reach.

Russia's inability subdue Ukraine in a timely manner and US et als destabilising campaign WW is highly effective. Eg Iraq, Syria, Ukraine, Latin America. The US and it's juniors don't need to be completely resilient if they can sow chaos abroad and at home?