China, Russia, and Iran—what is the common denominator? Most obviously, they are the main geopolitical rivals of the United States today. As Ross Douthat recently wrote in an NYT opinion, Who Is Winning the World War?, “it’s useful for Americans to think about our situation in global terms, with Russia and Iran and China as a revisionist alliance putting our imperial power to the test.”

Today’s post is about a much less appreciated similarity, having to do with deep history of these Eurasian empires.

As I have argued in a series of publications over the past 20 years, and most comprehensively in the forthcoming book, the main driver of “imperiogenesis” (processes underlying the rise of empires) is interstate competition. The intensity of this competition, in turn, is dialed up by advances in military technologies. Each military revolution, thus, generates a set of mega-empires. Today we live in the historical shadow of two most consequential military revolutions.

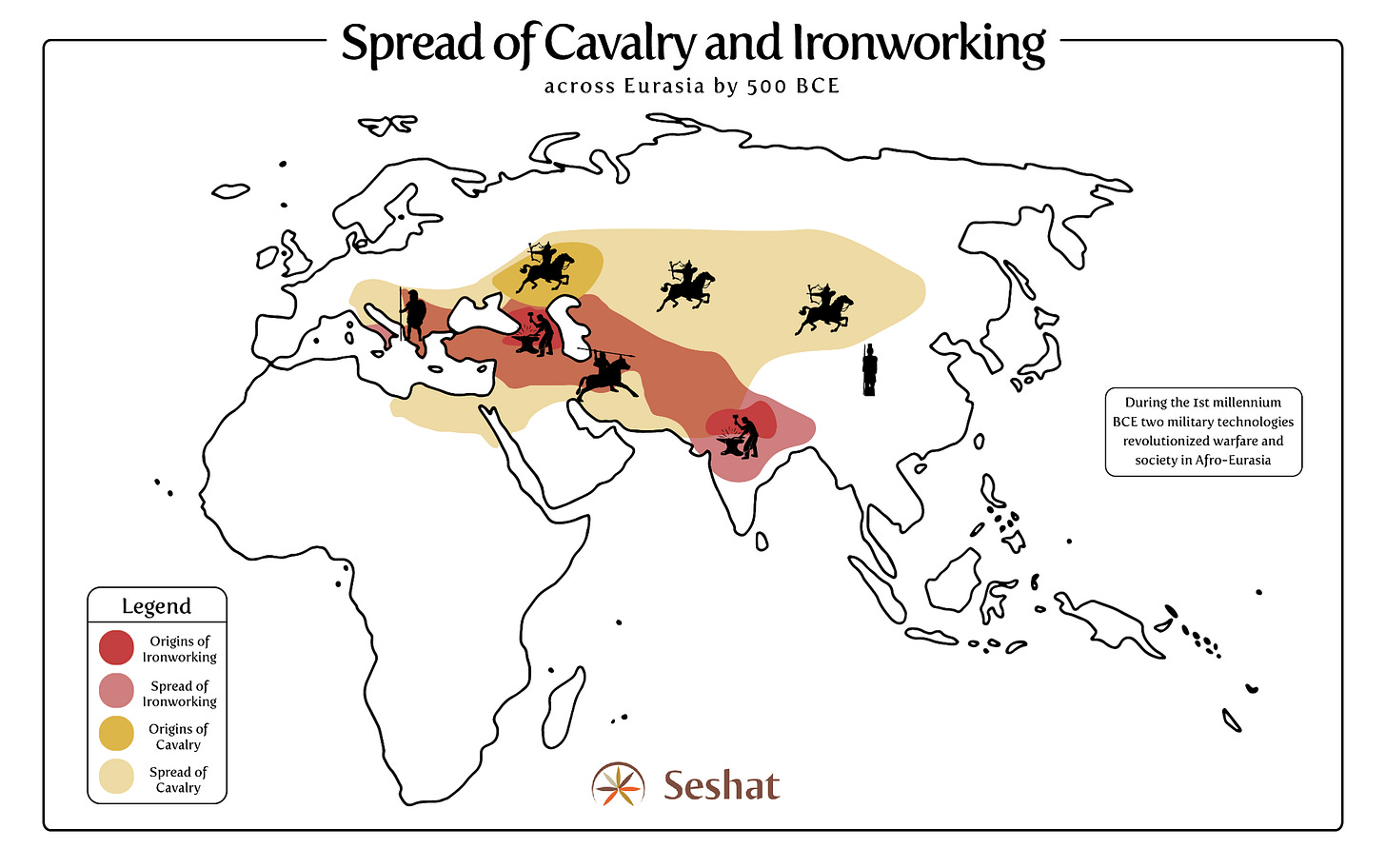

The iron-cavalry revolution dates to about 1000 BCE. Although horse riding and iron smelting were invented independently (and in different regions, see the infographic below), by 500 BCE they were spreading together (for the spread maps, see Figures 2 and 3 in our article, Rise of the War Machines). And the detailed story of this military revolution and its profound effects on world history are in my book Ultrasociety.

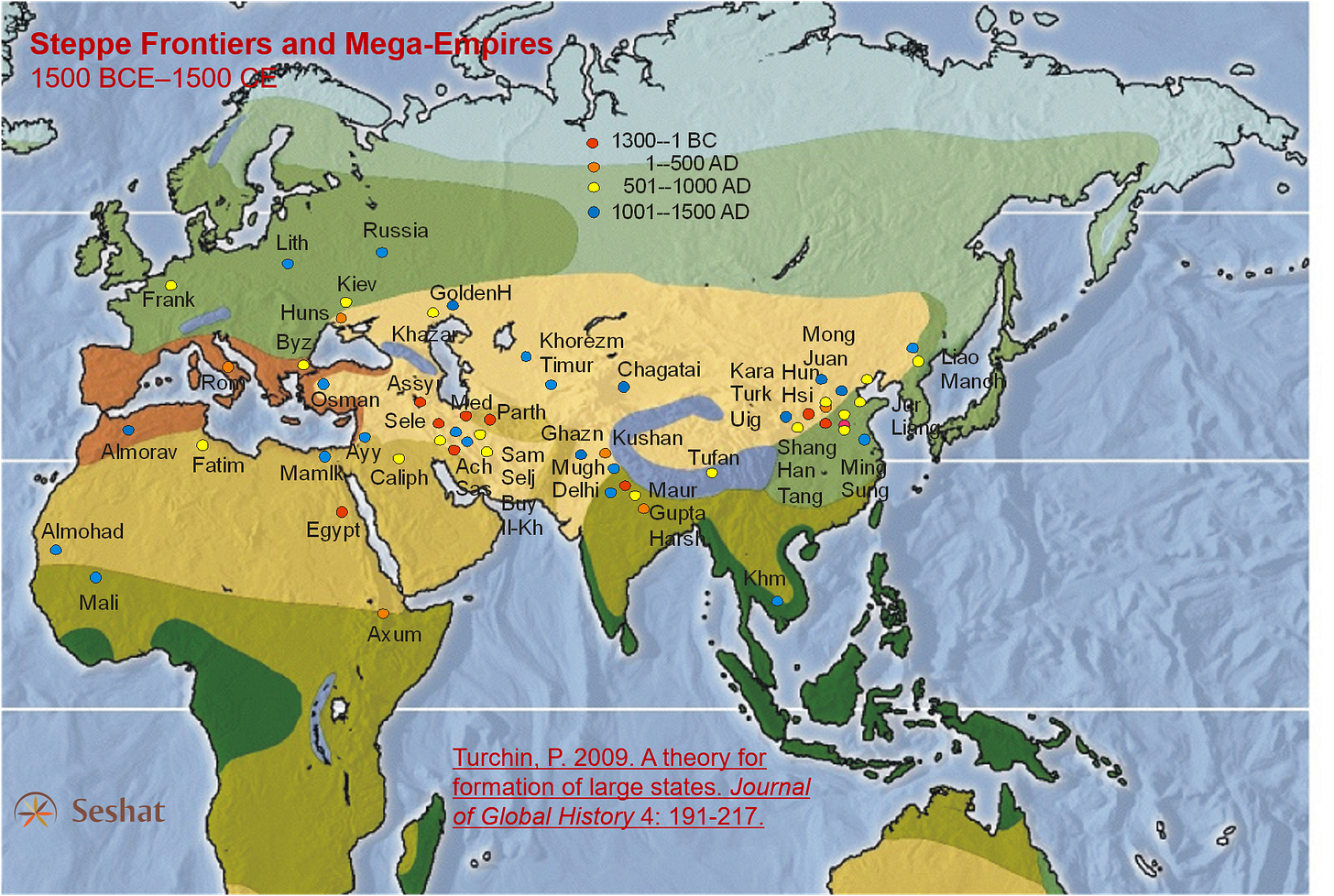

To cut the long story short, the iron-cavalry revolution transformed the Great Eurasian Steppe into an engine of imperiogenesis. This continental heartland was the home of nomadic pastoralists, whose main military force consisted of horse archers. Most of the premodern mega-empires were located on the “shores” of this “sea of grass” (see the second infographic below).

One such imperial cluster, north China, abutted the eastern steppe region (Greater Mongolia). Another cluster, Iran, faced the central steppe (Turkestan). The third, Russia, developed under the influence of the western steppe (the Pontic-Caspian region). Northeastern Europe was a bit of late-comer, because its forest regions acquired agriculture quite late (only by the end of the First Millennium CE). But what unifies all three imperial regions, China, Iran, and Russia, was that they all developed in close interaction with the Inner Asians.

The other consequential revolution was, of course, the one that originated in Western Europe around 1400 CE. It’s two components were gunpowder weapons and ocean-going ships. So I refer to it as the “Gunship Revolution.” The parallels between the two revolutions are quite striking. Inner Asians rode horses and shot arrows, while Europeans rode ships and shot cannon balls. The world ocean played the same role as the “sea of grass.” Historians noted these similarities. For example, the historian of Southeast Asia, Victor Lieberman, referred to Europeans as “White Inner Asians.”

Readers, who are familiar with geopolitical theories of Mackinder, Mahan, Spykman, and others (if not, check out this Wikipedia article), will immediately recognize the similarities between what I am talking about here and various geographical concepts central to these theories (the Heartland, the Rimland, the Islands…). What my historical analysis shows is that the conflict between the American Empire and China+Russia+Iran was shaped by the two great military revolutions, thus clarifying and refining the traditional geopolitical theories.

Thus, the Great Steppe (which is treated as a pivotal region by several geopolitical theories) today is of little significance, except for its historical effect. By 1900 it was completely taken over by Russia and China. Today it’s home to a bunch of weak and geopolitically insignificant states, such as Mongolia and the “Stans.” The successors of old mega-empires, which arose on the Steppe frontiers, is where Eurasian power now resides.

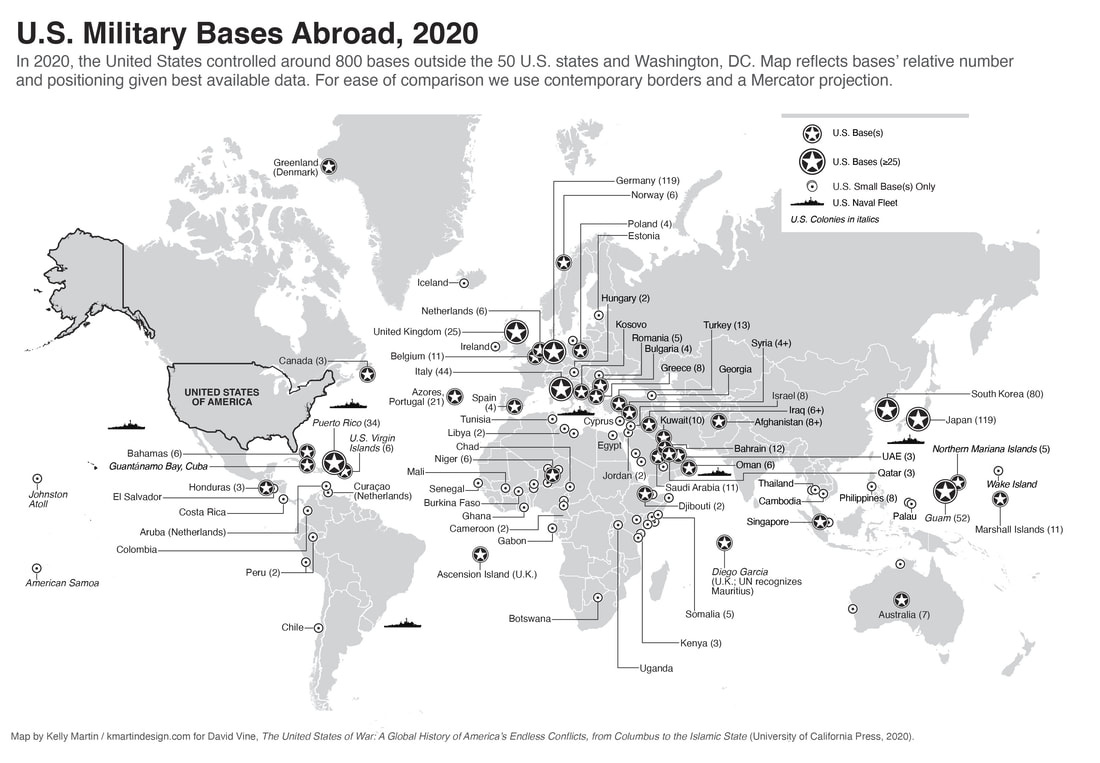

The second pole of power is “Oceania,” which originated on the western shores of Eurasia during the sixteenth century (Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands, and the British Isles), then spread across the Atlantic, and now is a global empire, ruled from Washington and Brussels as a secondary capital (although there are cracks between these two seats of power due to Donald Trump’s policies). A good way to visualize this geopolitical entity is a map of American military bases.

Oceania’s geopolitical logic—encirclement of Eurasian empires—is obvious.

As I mentioned above, the unity of this Oceania has been somewhat undermined by the policies of Donald Trump. On the other hand, it is important not to overstate the unity of the Eurasian imperial belt, either. The main reason for a pretty tight current alliance between China and Russia is the geopolitical pressure from America and its allies. Iran is both the weakest member of this triad, and the least integrated with the other two (although it will likely change in the future, as it is under a lot of pressure from the Israel/USA tandem).

This brings me to a final observation. Unlike imperial land powers, plutocratic sea powers are traditionally reluctant to use their own citizens as cannon fodder. Thus, Italian merchant republics relied on mercenaries. The British Empire preferred to use native troops, such as the famous Gurkhas. The American Empire today is reluctant to use American soldiers in hot wars, and thus tends to rely on client states: Taiwan against China, Ukraine against Russia, and Israel against Iran.

So far this post has been mostly theoretical—explaining how the geopolitical landscape of the 21st century was formed by the deep history. But there are important policy implications, which I plan to address in a future post.

These kinds of historical connections can help us understand future associations, which is a possible part of the 2nd post.

It is helpful to view certain technological advances as a kind of internet of the past. A sharing or perhaps more accurately a forceful imposition of foreign ideas upon other cultures that lead to further synergy.

As described with iron wielding horsemen imposing themselves upon central Asian society, many believe music, language, writing and trade further drove human relations and deepened integrity. The silk road as a classic example that provided all of these aspects of our shared humanity.

Persian and Chinese culture are thousands of years old whose roots lie deep within the human milieu. Russia a relative "newcomer" in terms of Xi'an or Persepolis yet is perhaps the bridge between the other two.

I believe the future is electric, not fossil fuel based. So we are seeing a slow deterioration of the old methodology and a birthing of a new one. It really is an amazingly impressive feat for the US of the 21st century to impose its military plunder regime across the entire globe, yet the synergy of the human condition remains.

Thank you for posting professor Turchin.

As for me, this particular excursion of yours (about the steppe and the empires on its outskirts) is a great and significant extension of Lev Gumilev's approach to the Great Steppe and the countries with which it borders. Anyway, I'm already looking forward to the sequel.