The Creation of Peace

In Human Evolutionary History

Happy 4th of July! Today’s post will be optimistic, for a change. As an aside, because my research on societal and state breakdown has received a lot of press, I’ve become a sort of “Professor Doom.” This is certainly a “big question.” But an even more important big question that I work on is why the overwhelming majority of humans today lives in large-scale complex societies organized as states. And, in fact, most of the time modern states work reasonably well, and some, like Denmark or Austria, are actually very pleasant places to live in, as I can attest from experience. Understanding the long-term social evolution towards large-scale societies is important, not least because it can help us to exit from our current crisis without too much bloodshed.

My topic today, the creation of peace, may sound inappropriate, given that there are so many wars actively fought in different parts of the world. In fact, the optimism, among certain circles, in the early 2000s that wars are over and peace is breaking out all over, was misplaced.

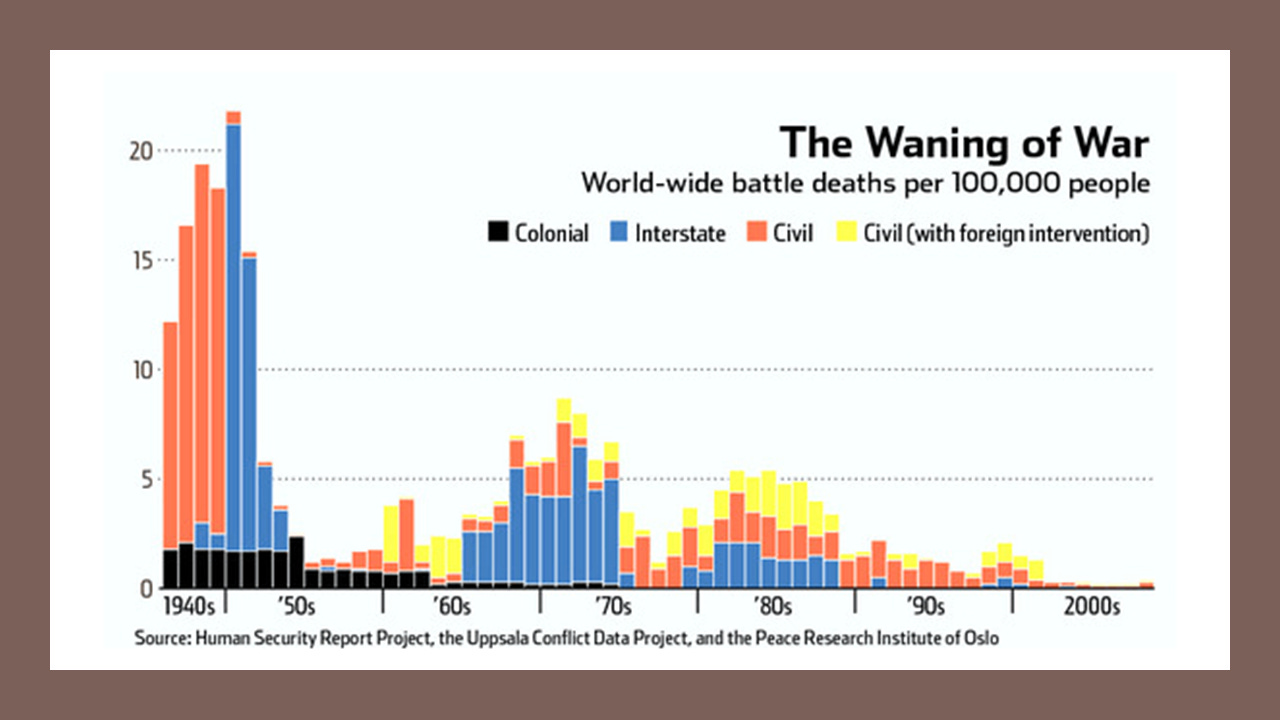

The key originator of the Decline of War thesis was the Human Security Report project, with a major report published in 2005. Steven Pinker in The Better Angels played a major role in popularizing the thesis. Here’s a typical example of data that were used to support the idea:

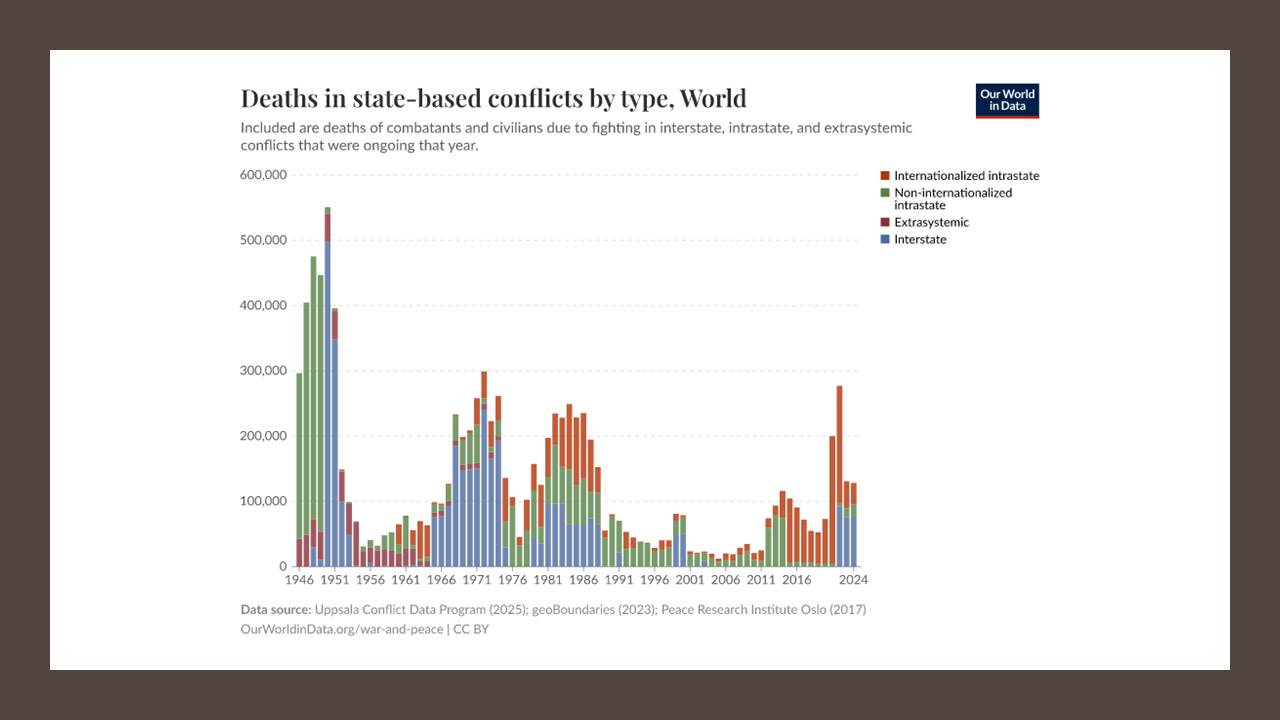

Unfortunately for the thesis proponents, post-2010 developments completely reversed the pre-2010 decline of war. The most recent report from the Uppsala Conflict Data Program documents a sharp increase in conflicts and wars. Here’s the graph from Our World in Data (incidentally, as I remember, Max Roser, the founder of OWID, was one of the most enthusiastic promoters of the Decline of War idea around 2010).

Thus, the trajectory of warfare is not linear and more contingent on structural forces and cycles than many had hoped. It is clear that in the short-medium term (years, perhaps a decade or two) we will need to survive both outbreaks of intrastate and interstate wars.

But let’s take the long view. What do we know about the evolution of violence in human history, on the time scale of thousands of years?

This is an extremely controversial subject, with most clashes between adherents of two extreme positions. The first is the Rousseauean myth of the peace-loving “noble savage.” Even when such “savages” fought, their wars were somehow considered nonlethal and nonserious, even comic affairs (according to the Eurocentric notion of “primitive war”). I demolish this myth in Ultrasociety (chapter 6, largely channeling Lawrence Keeley’s groundbreaking 1997 book War Before Civilization).

The opposite extreme is the view that the distant human past was an unrelenting Hobbesian “war of all against all.” This position has been occupied by Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, where he writes (in chapter 1), “If the past is a foreign country, it is a shockingly violent one. It is easy to forget how dangerous life used to be, how deeply brutality was once woven into the very fabric of our lives.” Pinker’s thesis also has been subjected to much criticism by academic anthropologists.

My view, developed in detail in Ultrasociety, can be briefly summarized as follows. Rates of lethal violence, both within groups and between groups, were generally low during the Pleistocene (the geological epoch preceding the Holocene, from 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago. It was characterized by a series of Ice Ages recurring with rough periodicity of 40,000–100,000 years). The primary reason was the sparsity of humans on the ground. Thus, a recent estimate suggests that the total human population in Western and Central Europe during the Aurignacian (42–33 kya) was between 800 and 3,300 individuals (see Population dynamics and socio-spatial organization of the Aurignacian). This population level is six orders of magnitude (that is, one-millionth) lower than the population count there today. At such a low population density, the potential for violence-starting conflicts is very low, and humans from other groups are more valuable as potential cooperators rather than potential competitors. Additionally, we know that most humans are averse to violence, and it takes training and combat experience to turn them into killers. The small proportion who were intrinsically capable of lethal violence (e.g., sociopaths) were controlled by within-group mechanisms.

Before discussing the developments in the Holocene (the current geological epoch), it is worth introducing a distinction between “positive peace” and “negative peace”, which was made by Johan Galtung in a 1969 article. Positive peace is the condition when violence is actively suppressed by strong and efficient peace-imposing organizations. Negative peace is simply absence of war. Because during the Pleistocene there were no suprapolity organizations (to our best knowledge), the conditions of relatively low levels of between-group violence can be characterized as negative peace. Such peace was fragile, and when human populations began increasing due to the climatic stability of the Holocene, the inevitable conflicts triggered spiraling revenge and counter-revenge cycles. In the absence of positive peace organizations, the logic of group survival required becoming warlike, as groups refusing to fight were eliminated. Once warfare started, it spread despite the peaceful inclinations of most people. Note that this argument doesn’t imply that violence was maintained at a uniformly high level; rather, the expected dynamic pattern is boom-and-bust cycles (see Was warfare responsible for the fall of small-scale societies?).

What happened next was that “10,000 years of war made humans the greatest cooperators on Earth”—as the subtitle of Ultrasociety says. Paradoxically, the spread and intensification of warfare during the first half of the Holocene created conditions for the evolution of institutions of positive peace during the second half. The primary causal factor was the expansion of the social scales on which humans cooperate. This was a result of several trends. First, the scale of polities and suprapolity organizations (e.g., alliances, leagues, and personal unions) increased by many orders of magnitude. Second, as states accumulated institutions, their peace-enforcing organizations (the judicial system and the police) became more efficient. Third, states became more responsive to the needs of citizens and gradually evolved from being merely engines of collective survival by adding functions to generate broadly based well-being (declining structural inequalities were an important part of this trend). Fourth, social norms suppressing interpersonal violence and promoting cooperation spread as part of the “civilizing process” (this idea is due to Norbert Elias).

This “ultrasociety” theory predicts a complex, dynamic pattern of violence trends during the Holocene. Let’s define “violence rate” as the probability of violent death resulting from all kinds of conflicts between people: interpersonal violence (homicide), intrastate warfare (riots, insurrections, and civil wars), and interstate wars. Violence rates were low in the early Holocene and then increased in the mid-Holocene, triggering the formation of larger-scale societies organized as states. Thereafter, violence rates experienced a series of peaks and valleys.

Valleys resulted when states were strong, suppressing internal warfare and homicide while fending off attacks from external enemies. Peaks occurred when states experienced disintegrative periods. Another mechanism that could result in peak violence was a military revolution that intensified warfare. However, the magnitude of peaks gradually decreased from the mid-Holocene levels. This was a result of accumulation of positive-peace institutions and, most importantly, the increased social scale of polities and suprapolity organizations. Even though polities fought increasingly intense wars against other polities, the effect of such warfare on violence rates was offset by the larger scale of such political organizations and their tendency to restrict warfare to peripheral regions—frontiers. For any geometric shape, as its area increases, the perimeter–area ratio decreases. Since external warfare is approximately proportional to perimeter, while total population scales with area, this principle implies that overall rates of violence due to external warfare decrease with the scale of polities. Put simply, by shifting military operations to the frontiers, larger empires protect a larger proportion of their populations from warfare.

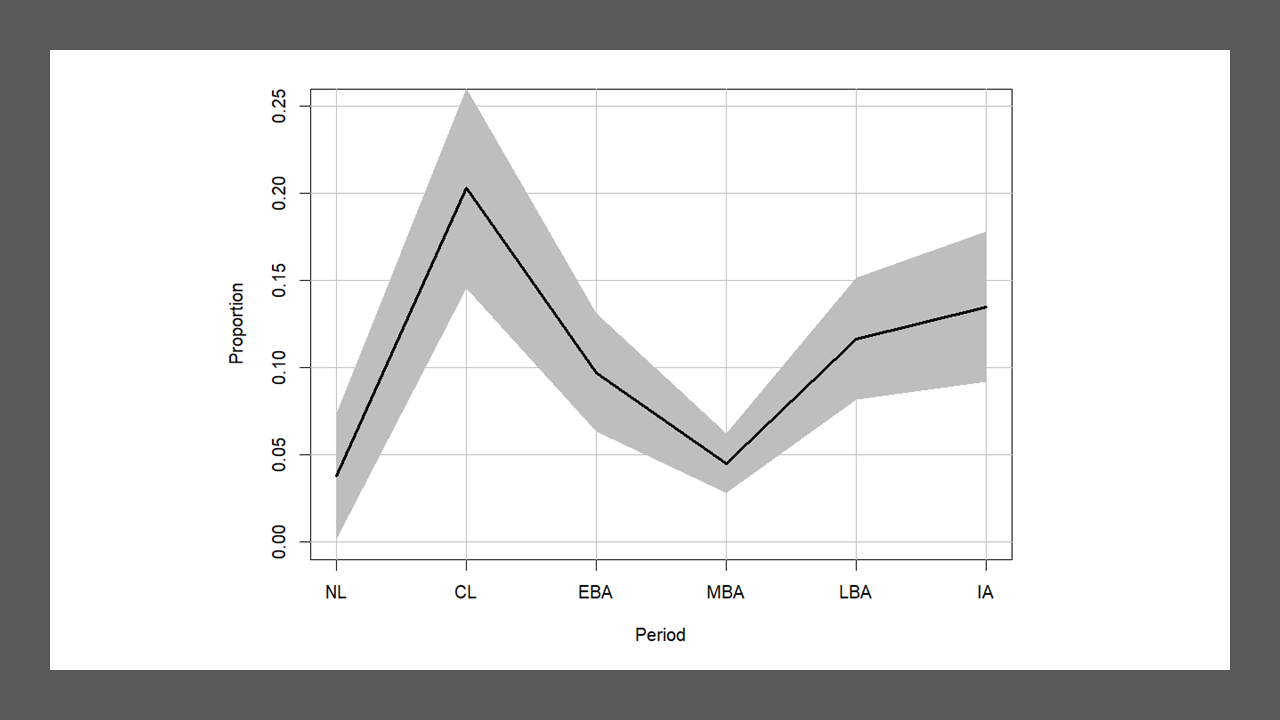

What do data tell us about this theoretical prediction? Until recently, researchers had to rely on a heterogenous assembly of empirical studies spread over different geographical regions and time periods. More recently, we began seeing systematically collected data covering a particular region over a lengthy period of time. An example is the 2023 study by Jörg Baten and colleagues, who systematically surveyed evidence for violent trauma in 3,500 skeletons excavated in the ancient Middle East (between c. 12000 and 400 BCE). The dynamic pattern in these data is consistent with the theory explained above (see the graph).

Trends in violent trauma in the ancient Middle East (includes the modern countries of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and Jordan). On the y-axis: proportion of skeletons with violence-related injuries (means ± SE). Periods (all BCE) are NL: Neolithic (12000–4500); CL: Chalcolithic (4500–3300); EBA: Early Bronze Age (3300–2000); MBA: Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550); LBA: Late Bronze Age (1550–1200); and IA: Iron Age (1200–400). Source.

In particular, we see a very low level of violence during the first half of the Holocene, followed by a sharp rise in the mid-Holocene (Chalcolithic, 4500–3300 BCE). The Bronze Age empires brought down the violence to the early Holocene levels. However, the imperial breakdown in the Late Bronze Age and, especially, the military revolution of the Iron Age brought a return of violence, although not to the same level as the first peak.

The implications from this (empirically supported) theory is that the current outbreak of violence will have an end—“this too shall pass.”

Dr Turchin, you may be 'Profesor Doom' to the media class in their bubble who thought everything was fine until very recently; but to those of us in the working classes who can feel everything breaking and want the people running things to do a better job, it's quite the opposite: you actually bring hope.

I especially appreciate the effort you go to to bracket your own politics in order to follow the models and the data wherever they take you. I know that is hard and few academics are willing to do that these days.

There's a recent BBS article about the evolution of peace in humans focusing on the factors required before our species could create peace and speculating when it might have occurred: The evolution of peace. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2024;47:e1. doi:10.1017/S0140525X22002862