Structural-Demographic Cycles in Morocco

Ibn Khaldun rules

Yesterday was a nice break from a generally rainy weather in Marrakesh, and we used this opportunity to wander around the old city. The most spectacular landmark here is, of course, the Koutoubia Mosque (using the French spelling), whose minaret tower can be seen from miles away.

Photo by the author

Marrakesh was founded around 1070 by the Almoravids, and served as the capital for this dynasty until the Almohad conquest. The first mosque on this site was built by the Almoravids, but when the Almohads took over, they demolished it. Apparently, the new dynasty disagreed with the mosque’s orientation (for a long and confused explanation of this controversy read this Wikipedia article). The currently standing minaret dates from the late 12th century. A very impressive structure.

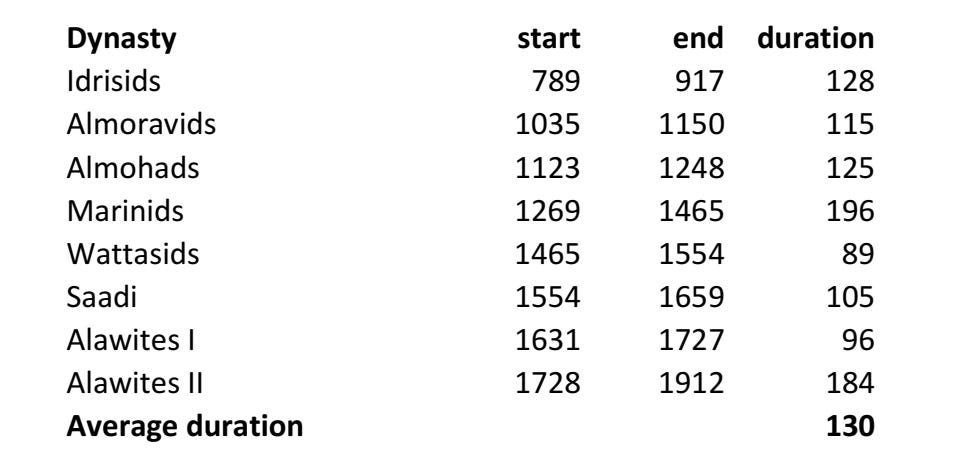

One of the reasons I am fascinated by the Moroccan history is that it provides a very nice illustration of a strong empirical pattern in Cliodynamics. Take a look at the table below, listing the Islamic dynasties, which ruled Morocco, and their dates.

A new dynasty comes from the desert, conquers the “civilization” — the land of cities and states in the North African littoral, where rainfall is sufficient to support agriculture. For a while (typically, two-three generations), the new dynasty rules well. But eventually it becomes degenerate. Its fourth or fifth-generation rulers are then overthrown by a new vigorous group from the desert, and the cycle repeats.

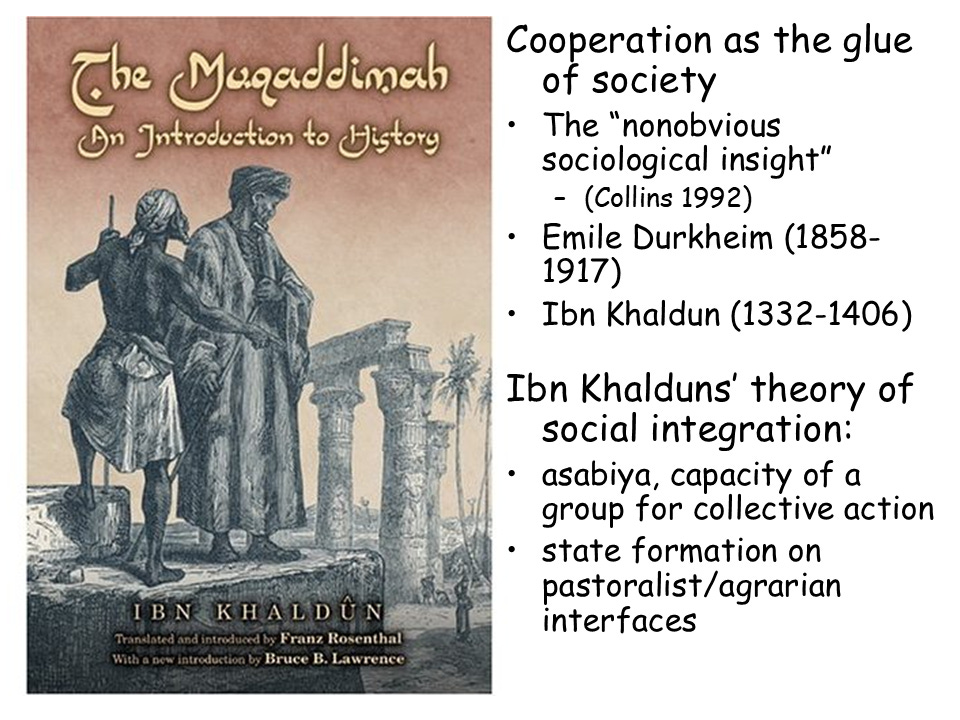

This pattern was first noted by Ibn Khaldun, the 14th century’s Arab sociologist and a precursor of Cliodynamics. I wrote at length about him and his theories in War and Peace and War.

This is a slide in one of my talks where I discuss Ibn Khaldun

Readers familiar with the structural-demographic theory will immediately see that the Ibn Khaldun cycles is a variation on the secular cycles that affect all state-level societies. But such cycles of Islamic dynasties are, on average, much shorter than secular cycles in, for example, Christian states. The average dynasty duration in the table above is 130 years, whereas the typical length of secular cycles in Europe was between 200 and 300 years. Why?

It turns out that the explanation of this pattern is also provided by the structural demographic theory. Whereas Christianity limits a man to one wife, in the Islamic world the elites tend to have many wives — up to four “legal” wives, plus as many concubines as a man can support. As a result, the elites in Islamic states tend to produce multitudes of sons, which results in a very rapid process of elite overproduction. As a result, dynasties in polygynous societies (one man—many wives) tend to cycle much faster than dynasties in monogamous societies (one man—one wife). The nice thing about this explanation is that it doesn’t require any appeal to “mystical” mechanisms such as the loss of “dynasty vigor.”

As a final thought, you may be interested in a related old post on this theme:

Excellent post! This made me think about monogamous versus harem style animal societies and whether similar dynamics are at play there. For example, the silverback male gorilla "rules" over a harem of females and their offspring (including his sons), until he is overthrown. In chimpanzee societies, a coalition of males "rule" until they are overthrown. What are the dynamics of leadership turnover in these differently structured ape societies, and do they also support the cliodynamics that are observed in humans (obviously without the written history of "clio"). And there's evidence that individuals within family lines can even inherit "wealth" of a sort (good breeding grounds, nests, accumulated cultural artefacts, etc.), creating culturally heritable differences in privilege -- See: Smith, J. E., Natterson-Horowitz, B., & Alfaro, M. E. (2022). The nature of privilege: intergenerational wealth in animal societies. Behavioral Ecology, 33(1), 1-6.

Interesting. A few observations.

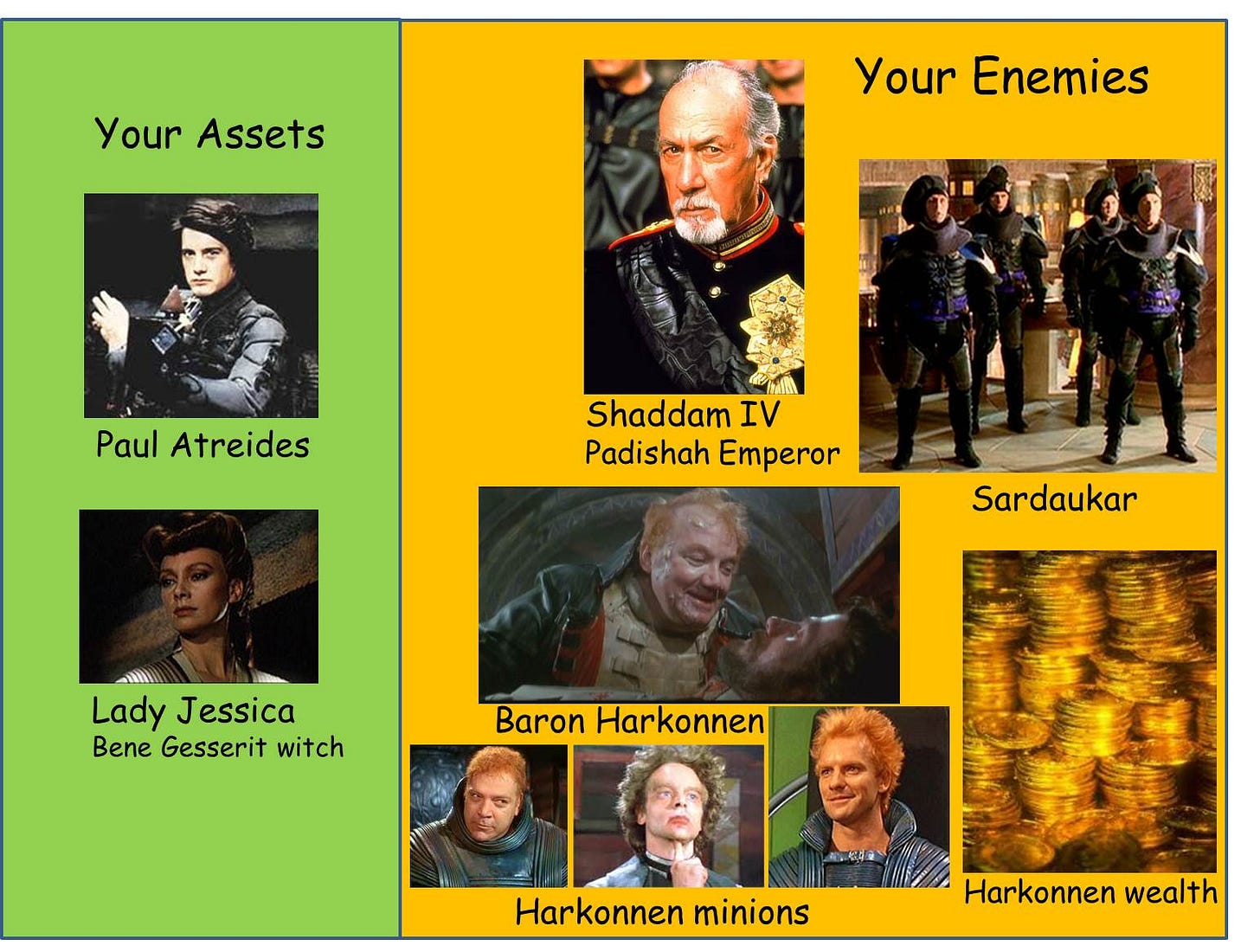

It’s hard to read Dune without suspecting that Frank Herbert was engaging Ibn Khaldun directly, rather than converging on similar ideas by coincidence. The parallels are numerous and structural, not superficial. I’m curious whether Herbert ever explicitly acknowledged this influence.

What’s especially striking is how deeply Herbert understands the dynamic. Early in Dune, Leto Atreides recognizes the origins of the Sardaukar on Salusa Secundus (a horrendous prison planet mislabelled by all subsequent TV and film adaptations) and accepts the poisoned chalice of Arrakis to replicate that formative pressure through the Fremen. His enemies assume he has fallen for the “honey trap” of spice wealth. He has not. He is playing a different game entirely.

Leto understands that Caladan cannot produce the military power he needs, and that refusal of the Emperor’s offer still leads to destruction. This is the key point: declining the trap does not restore equilibrium. He recognizes that he is already at war and on his way to losing before any shots are fired. Very Sun Tzu.

That recognition is both admirable and tragic; reminiscent of Winston Churchill enduring years of accusations of warmongering before history caught up. This is leadership under extreme constraint: seeing the full board, recognizing that all options are bad, and choosing the one that preserves a narrow path to survival.

Leto understands how the Emperor truly controls the Imperium (through the Sardaukar) and concludes that an alliance with the Fremen is worth the risk precisely because not taking that risk guarantees defeat.

It’s been many years since I read the later books, and I never finished God Emperor, so I’m not sure how explicitly Herbert later foregrounds this logic. But it’s already fully present in Dune itself.

One final note, on a lighter front: the Sardaukar were never meant to look like Parisian fashion victims. Thank God for Denis Villeneuve.