On Taking Sides

Most “Analysis” on China is Projecting Own Biases

Last week Arnold Kling reacted to my post So, It’s China. His response was titled Turchin vs. Zeihan on China. Game on; and Noah Smith says that China will underwhelm. I don’t disagree with Kling on the substance of what he wrote, but I take issue with the “Turchin vs. Zeihan” part. In no way my post was an argument against Zeihan personally (I am sure he is a fine human being). In any case, I don’t have the expertise on modern China to make a strong argument against anybody; I merely pointed out that Zeihan’s forecasts on the impending collapse of China were wrong (so far).

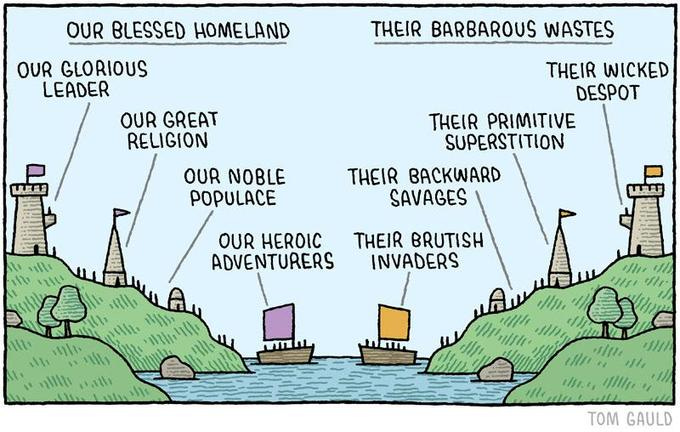

This brings me to a more general point. Most analysis one sees on China is extremely partisan: some set out to prove that China is bad and, anyway, in trouble; others take the opposite task, that everything is just peachy in China.

Actually, the worst offenders are the first group. Pro-China views, at least those that I see, tend to be less strident and more factual. As an example, mentioned in my post, is Arnaud Bertrand, whom I read on X and generally find quite reasonable. His bias is mostly in the selection of themes, which tend to be positive on China.

Noah Smith, whom Kling mentions in his post, is a different matter. I actually enjoy reading his posts on economics and science fiction, but his geopolitical analysis is simply channeling the official US propaganda, which you might as well get directly from the New York Times.

A major premise of my Substack is that I strive to be as even-handed as possible. We are all human and, undoubtedly, I have my own biases. Thus, I’d appreciate readers pointing them out. But at least I try. This is important. Scientists are taught in graduate school that when testing theories in science (and this blog is about science), we need to avoid biasing results in favor of our favorite explanation. Of course, scientists being human break this rule all the time. The saving grace is that science is a collective endeavor and the truth emerges from controversies, when opposing views clash.

This is also my approach. When I want to understand China, or any other contentious issue, I purposefully seek opposite opinions. I actually periodically play with an idea to make a formal comparison of two (or more) explanations a regular feature in this blog, but so far I’ve not got around to it. It’s a lot of work to do it properly.

I can’t find the link, but some time ago I read about somebody using formal Bayesian analysis to resolve questions such as the origin of the Covid virus. But I wasn’t particularly impressed—there are too many real-life obstacles to making such an analysis both rigorous and meaningful.

Meanwhile my research team has started gathering data on China. There are two major sources of uncertainty: (1) what are the meaningful indicators and (2) how well we can get quantitative data on such indicators.

I am looking forward to navigating these difficulties and you will be the judge of how well I succeed. But don’t expect it soon; a lot of work and thought will need to be invested to produce a meaningful result.

Lots of discussion, much of it great! Usually, I try to respond to specific comments, but today I won't do it, because I don't yet have a factual basis for doing so. For people asking about the details of what I plan to do with China, they are, of course, in my books -- a popular (and more up to date) version in End Times, while quantitative and modeling results in Ages of Discord. I am planning to do the same for China, but with several differences, of course. One is data, as everybody acknowledges. The other is a completely different structure of power and elite formation. We shall see.

Please don't compare yourself to Peter Zeihan.

I’ve listened to several of his podcasts, and his arguments are riddled with factual errors and inaccuracies. eg here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UltVl2Qlf6A&t=314s he states that China "imports 75-80% of its energy" while the actual share of imported energy vs total consumed is ~20-25%. More appalling as he fashion himself as an expert of demography, on the same interview he states that China "has more people > 53 than under" (China's median age is 39).

Beyond his clear ideological biases, he lacks any credentials that would qualify him as a legitimate expert.