The French Wars of Religion I

A nearly perfect example of a structural-demographic crisis (Part I)

One reason (perhaps the most important one!) for my enduring interest in history, which eventually led me to Cliodynamics, was that my favorite book genre as I was growing up was historical romances. Today, now that I have a much better understanding of processes driving historical dynamics, I realize that the overwhelming majority of these novels took place during the disintegrative (crisis) periods. As an example, two of my favorite novels were La Reine Margot by Alexandre Dumas and A Chronicle of the Reign of Charles IX by Prosper Mérimée. Both describe intraelite conflicts during the French Wars of Religion (hereafter the FWR).

Henry of Navarre and Margaret of Valois Source

I asked ChatGPT to give me a one-sentence explanation of the causes of this bloody and lengthy civil war. Here’s what it said: “The French Wars of Religion were primarily caused by growing tensions between Catholics and Protestants (Huguenots) in France, fueled by religious intolerance, political rivalries among noble families, and a weak monarchy unable to maintain order.” This answer perfectly encapsulates the standard story as seen in popular historical books, or online encyclopedias (LLMs, such as ChatGPT, are great at summarizing such common wisdom).

Readers of my books and blog posts would immediately realize that Cliodynamics gives a very different answer. Noble rivalries and religious tensions were what happened on the surface. But the deep structural causes of the FWR were popular immiseration, elite overproduction leading to intraelite conflict, and fiscal collapse of the state. In other words, the usual suspects when we talk about structural-demographic crises.

The Day of the Barricades (Paris, 1588), an ostensibly spontaneous popular uprising, which was in reality organized by counter-elites Source

What I’d like to do in this post series is delve a bit into these structural causes (for a deeper dive read Chapter 5 of Secular Cycles). I have two reasons to do so. First, the onset of the FWR gives us a nearly perfect example of how structural-demographic trends lead to state collapse and civil wars. Second, it was the fiscal collapse of the state that triggered warfare in c.1560. I wrote about the possibility of such a trigger for the America today in a recent post, where I concluded that we are fairly immune against it. But France in the sixteenth century was, most emphatically, not immune.

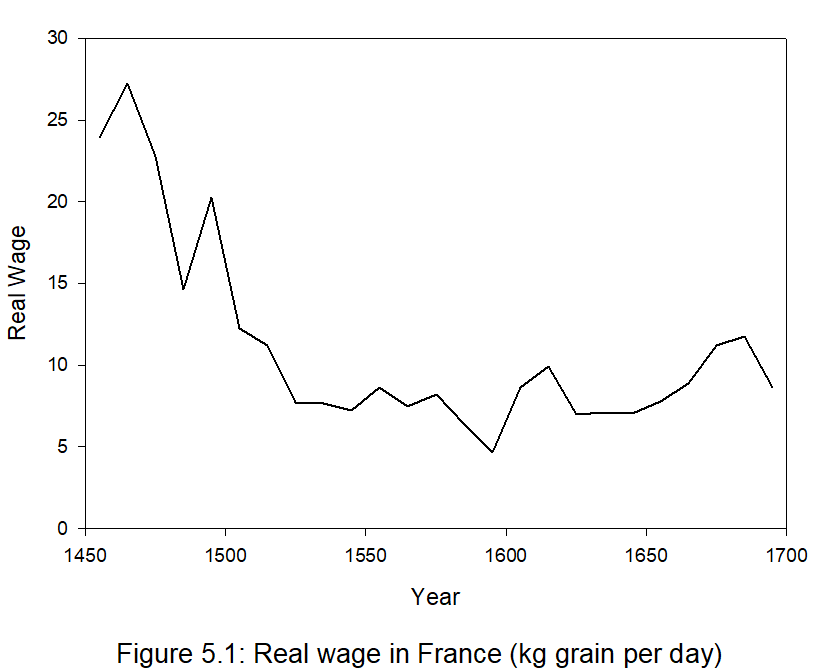

The ultimate driver, as usual in agrarian states, was population growth. During the integrative phase of the cycle (1450 to 1560) the population of France doubled: from 10–11 to 20–22 million. The French Kingdom in the sixteenth century was an overwhelmingly agrarian state and agricultural productivity couldn’t keep up with such massive population growth. As a result, food prices exploded. The price of a setier (a measure of volume) of wheat in livres tournois (the standard monetary unit in early-modern France) increased 10-fold between the 1460s and 1560s. Overpopulation created a high demand for food, inflating its price, and it increased the supply of labor, deflating its price. During the sixteenth century real wages lost two-thirds or more of their buying capacity. The daily wage of the Parisian laborer could buy 16 kg of grain in the 1490s, compared to less than 4 kg one century later.

Real wage in France, 1450–1700, in kg of grain per day. The real wage is calculated by taking an average of the wages paid to laborers and craftsmen in Paris, as reported by Allen (2001), and deflating them with the price of wheat (Abel 1980). Source: Chapter 5 of Secular Cycles.

While the general population immiserated, land-owning elites prospered, as the products of land, such as grain, increased in price, while the price of labor decreased. This favorable economic conjuncture for the elites resulted in two related developments. First, growing inequality among commoners meant that although the great majority of them were sinking into misery, a small minority, profiting from low wages, did very well and acquired substantial wealth. These well-to-do commoners, wealthy farmers and merchants, naturally aspired to translate their wealth into elite status. Many such elite aspirants succeeded, generating a steady inflow into the ranks of nobility.

Second, many noble families started to provide substantial inheritances to their younger sons. This practice led to estate subdivision and multiplication of nobles. For example, one of the richest French magnates, François de la Trémoille (1502–42) had to provide for five sons (and dowries for two daughters).

Driven by upward mobility and estate subdivision the numbers of nobles increased dramatically during the sixteenth century. For example, the numbers of the top elite stratum (pairs laïques—lay peers) tripled between1505 and 1588 (more detail in Part II of this series).

An inevitable result of this increase was intensifying intraelite competition for status and wealth. One way we can gage increasing pressures on the elites is by the incidence of intraelite violence, which during this period took the form of dueling. Dueling had almost disappeared in France during the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Under François I and Henri II a handful of judicial duels took place with royal sanction.

The duel between Jarnac and La Châtaignerie (1547). Henri II presides. The two combatants were members of the rival elite factions, Montmorency and Guise (more on this in the next installment) Source

After 1560, however, dueling for personal honor and without royal sanction became so common that it was believed that more noblemen died from it than in combat. Between 7,000 to 8,000 nobles were killed in the two last decades of the sixteenth century. It was said that Henri IV granted over 6,000 pardons for the killing of gentlemen in duels during just the first ten years of the seventeenth century.

Of course, duels loom large in the historical romances I read as a boy.

In the next installment, we will see how intraelite competition and conflicts led to the collapse of the Renaissance state in France.

Interesting comments below about the clash between Muslim and Progressive values, but need I point out that it is completely off-topic? The whole thrust of this post (and, more generally, the series) is that religion was _not_ a fundamental cause of the (misnamed) Wars of Religion. If you need further proof, just consider how easily most Protestant leaders switched to Catholicism, when it suited their pragmatic goals. Henry of Navarre switched twice. "Paris is worth a mass", indeed.

Thanks for this article. Indeed I learned a lot about the history of France from your books, which although being French, I did not know.

It would be great if you could some day write about the current situation in France. It's not per se a war of religion, but the role anti Muslim rethoric takes in current French politics has been incredible for decades. I do not know of another country where debates can be has heated about where women could be allowed to wear hijab or not. In France for eg mothers who want to help teachers on a school event are not allowed to wear hijab, nor girls at school, they are not even allowed to wear anything ressemling a Muslim dress at school. Some years ago there was a huge debate about burkinees on the beach, and they were forbidden too. There seems to be a sort of obsession in France about what Muslim women can wear or not, very disproportionate, because women should be able to wear what they please.

In short, French politics seems obsessed with religion, which is strange in a country where probably almost half of the population is actually atheist...