The Controversy over Multilevel Selection

Science Proceeds by Paradigm Shifts

One of the longest enduring controversies in evolution is about what was initially called “group selection,” but for reasons I explain below is better referred to as “multilevel selection” (MLS).

Originally, group selection referred to the idea that natural selection can act on groups (as opposed to individuals or genes). It was used to explain how evolution could favor traits that benefit the group even at an individual cost. A particularly important question was to understand the evolution of cooperation. Early formulations (most notably, by V.C. Wynne-Edwards) were quite naïve in that they simply postulated the benefit of cooperation for a group (or even whole species) without considering that it was to the personal advantage of individuals to “free-ride” — to benefit from the fruits of cooperation without paying the cost.

Then, in 1964, W.D. Hamilton came up with the idea of inclusive fitness (also known as kin selection), which seemed to explain better most observed example of cooperation in the animal world, especially social insects. By the 1970s the first notion of “naïve group selection” was thoroughly discredited. An influential popular book in this shift of scientific opinion was Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene. This was a true paradigm shift, which quickly became a new orthodoxy.

But it is usual in science that paradigms replace one another. By the late 20th century, when I became active in this field, the anti-group selection dogma began fraying. Most importantly, the debate shifted to multilevel selection theory (MLS), which recognizes that selection can operate simultaneously at multiple organizational levels (genes, individuals, groups).

Today, in my estimation, the majority of evolutionary scientists view MLS either as a productive, mainstream framework (not fringe, with real explanatory value) or as conceptually valid, but not important, as kin selection does all the work. Only a minority still cling to the anti-group selection paradigm that had become dominant in the 1970s.

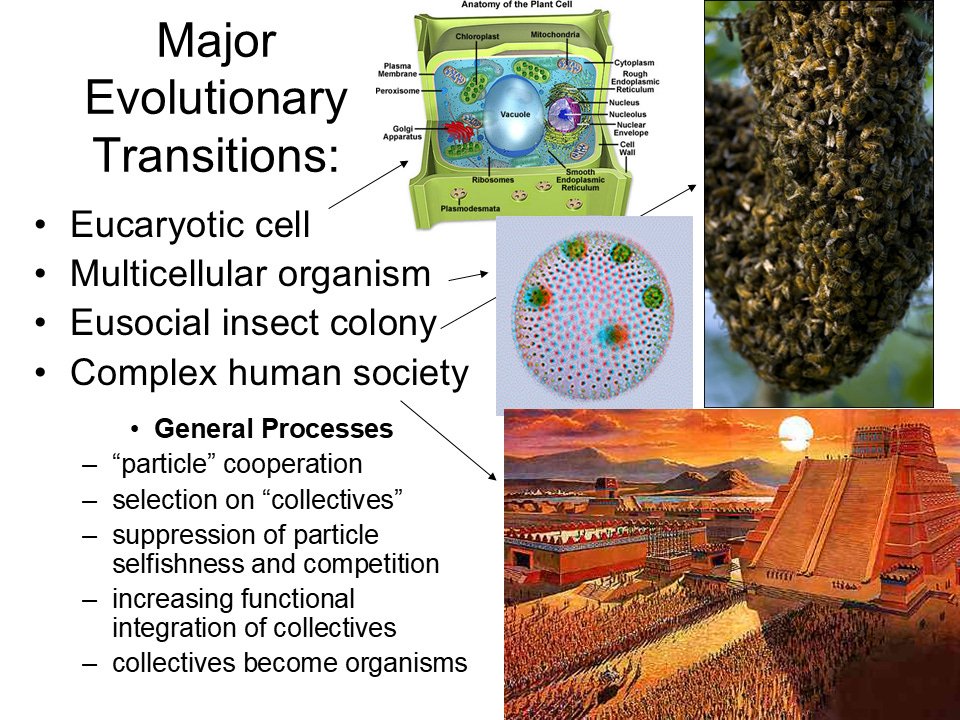

MLS is particularly useful in understanding Major Evolutionary Transitions. If you think about it, biological entities, except for the simplest ones, are all multilevel. Eukaryotic cells, such as the ones making up our bodies, evolved by a combination of simpler, bacteria-like cells. Cells are combined in organs, and organs are combined in organisms. Societies consist of many organisms.

Even the idea of gene-centric evolution doesn’t make that much sense, because genes are combined in chromosomes, and chromosomes are combined in genomes. Here’s a slide that I used in my lectures on the evolution of cooperation (when I was still teaching):

The last major attack on the MLS theory, that I know of, was the 2012 article by Steven Pinker, The False Allure of Group Selection. Since then the debate on multilevel selection has shifted in favor of the proponents of this theory. For example, in 2016 Peter Richerson and colleagues published a programmatic article on the application of MLS to cultural evolution. There was a variety of responses to this article, some favorable (including my own), others less so. But what is curious is that the irreconcilable critics of cultural group selection, Dawkins and Pinker, declined to contribute responses, even though they were invited to do so. A most recent development is an academic volume on MLS (currently in the works) edited by one of the most consistent proponents of this theory, David Sloan Wilson.

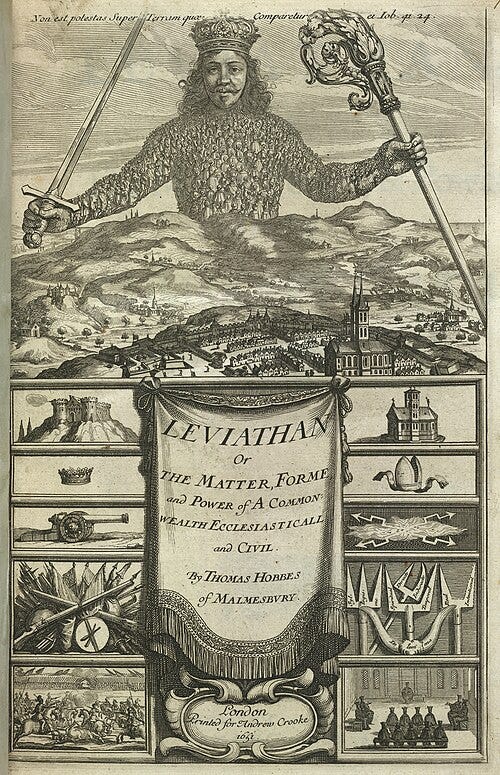

I wrote a chapter for this volume, in which I argue that polities — politically independent organizations of humans, ranging in scale and complexity from self-governing Neolithic villages, to chiefdoms, states, and empires — are a legitimate level for evolution to act on.

Frontispiece of Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes depicting the state as an organism Source

Indeed, modern states are quite organismal-like — but that’s a good topic for another blog.

What’s important is that we are clearly in another shift of paradigms, and that’s good.

Interesting...Only one mutation in 10,000 is even slightly favorable, and that gene has a good chance of being lost in the mating process..So evolution would normally be an extremely slow process, unless the owner of that gene had many offspring....Where do the interests of the group enter into this? The group would benefit from any gene that makes individuals fitter for their environment, but might lose if the gene also negatively impacted group harmony and coordination....On the whole, however, the first consideration will predominate...The superior hunter benefits the group a lot, while his antisocial tendencies can be dealt with...Whereas a mutation that makes him a better team player, while useful, will not be worthwhile if he isn't productive....So the gene will likely be lost if access to many mating opportunities isn't available...Who gets access in most groups? The high status male, a hunter or a warrior back in the days when even subsistence could be difficult...and that seems to have been the case in the Bronze Age...70% of modern Europeans, I have read, were descended from just 3 Bronze Age chieftains, while Genghis Khan has 20 million living descendants....

So I'm inclined to believe that fitness that leads to leadership predominated in the genetic competition up to the modern Welfare State society....and is probably being lost overall as fitter humans are having fewer children than their competitors....

D. S. Wilson, E. O. Wilson ... must keep your Wilsons apart. Here is mnemonic: "D" stands for "dad" of Katie Wilson, the current Seattle mayor. "E" stands for "entomologist" and hence the famous quip "great idea - wrong species"