Civilization without God

Religion and the Evolution of Complex Societies

In a recent post, Arnaud Bertrand argued that China, unlike Europe, had built a sophisticated civilization without religion at the center of its political life. This is an interesting thesis, which has apparently triggered much debate.

On one hand, it is true that there is a deep difference between the religious landscapes in Eastern and Western ends of Afro-Eurasia. In the West, we are very familiar with the idea of an all-powerful and all-knowing God, who created the universe and punishes human transgressions.

Art by ChatGPT

This specific idea, indeed, did not play an important role in the social evolution of China.

On the other hand, it’s wrong to say that religion was unimportant in China. Things are more complex, and much more interesting. I can speak with some authority on this subject, thanks to a multi-year Seshat project which involved many dozens of historians, archaeologists, and religion scholars.

This project began as a way to empirically test an influential idea in cultural evolution, known as the Big God Theory. Put in simple terms, large-scale complex societies require a certain degree of cooperation (and the more, the better) to function well without falling apart. Cooperation is difficult to achieve because it is vulnerable to the free-rider problem — those society members who are happy to enjoy the fruits of cooperation, but refuse to pay its costs. Cooperation requires enforcement; specifically, free-riders need to be sanctioned so that they contribute their fare share.

In small-scale societies, where everybody knows — and watches — everybody else, it is relatively easy to detect and sanction selfish free-riders. But who watches you in a large-scale “anonymous” society? The proponents of the Big Gods Theory (BGT) argue that this job is done by a supernatural watcher/punisher. God in Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) fits this role perfectly.

This is a very clever idea, but like any scientific theory, the BGT needs to be tested with data. And that’s what the Seshat project set out to do, beginning 10 years ago. Over those years we ran numerous workshops, consulted with many dozens of experts on past human societies around the globe and spanning many thousands of years.

Because “religion” can mean many things to different people, we focused on a more specific concept, “moralizing religion” which refers to “clusters of beliefs and practices postulating a system of supernatural punishment and reward for morally salient behavior, where such systems are primarily concerned with the way humans interact with other humans, rather than how they interact with supernatural forces” (ref). Moralizing Supernatural Punishment (MSP) refers to the presence of such beliefs and practices in any degree.

After a humongous amount of work coding this variable in all Seshat societies, we published a set of academic articles analyzing the causal interrelations between MSP and social scale and complexity. These articles, together with commentaries and responses, were published in a Special Issue of Religion, Brain, and Behavior (see Introducing a special issue on the role of moralizing gods in the evolution of socio-political complexity). I discuss our findings and implications in these posts on my blog archive:

What Came First: Big Gods or Big Societies? Round Two

Big Gods and Big Societies: A Closure

The academic articles that we published, by their nature, cannot give full justice to the amount of empirical material that our project distilled, thanks to the contributions of expert historians and religion scholars. So, what we did next, was publishing this material in a book form. In fact, there was so much interesting information that we had to publish this book in two volumes:

The Seshat History of Moralizing Religion: Volume 1: Historical and Comparative Perspectives

The Seshat History of Moralizing Religion: VOLUME 2: World Survey

And now I return to what I started this post with: has China, unlike Europe, built a sophisticated civilization without religion? To answer this question, we go to the chapter on China in Volume II. Here’s what we discover:

In the Late Shang (1250–1045 BCE) deities lacked any moralistic aspects, and we infer a similar absence of MSP in the preceding periods. Di, the “high god” of the Shang, was the god of rain, snow, hail, wind, thunder, and disasters.

The first appearance of MSP is the Mandate of Heaven (Tian) in the Western Zhou (1045–771 BCE). However, the primary concern of Western Zhou deities remained with ritual. Morality aspects were limited (and rather vague); punishment was uncertain and inflicted on whole groups rather than individuals; and dealing with Tian was the exclusive domain of the ruler.

During the Eastern Zhou, the concept of Tian was democratized by Confucians, but this development affected only a small segment of literate elites. Additionally, there was significant variation between different Confucian thinkers on Tian and its Mandate. Furthermore, in non-philosophical thought Tian was often portrayed as an amoral deity, or fate.

The Mandate of Heaven was officially adopted as the state ideology during the Han period. It was explicitly invoked by Wang Mang and later endorsed by the first Eastern Han emperor (first century CE). Nevertheless, Tian never evolved into a fully moralizing supernatural force/agent. According to conflicting interpretations, Tian could either punish transgressions directly or leave enforcement to human agents, and punishment could be either individual-focused or collective. Furthermore, all these MSP aspects are most relevant at the level of the state and elites.

Popular religion included its own versions of MSP, enforced by a variety of spirits. In common with many other religious traditions described in this volume, ritual transgressions were not clearly distinguished from antisocial behavior.

The rise of Neo-Confucianism c. 1000 CE encouraged the development of a more rationalistic and secular state. Song dynasty Neo-Confucians suggested that the emperor was not the center of the universe, and some even denied the Mandate altogether. The first Ming emperor, however, marked a return to a more traditional approach to the Mandate and Heaven worship. Thus, the interpretation of the Mandate was not consistent in Imperial China and was greatly influenced by shifting court ideologies. By the end of the Qing dynasty, it appears that both ritual behavior and good governance/the will of the people were key in maintaining the Mandate.

Fully developed MSP arrived in China with Buddhism, which started making inroads during the first century CE, first became the official ideology c. 300 CE, and became a mass religion during the Tang period (eighth century).

There are also aspects of MSP in Daoism, but it was not a cohesive religion or fully integrated in the state cult until after the introduction of Buddhism.

And this account focuses on the beliefs of the elites, although elements of MSP were widespread in the Chinese popular religion. For example, ghost stories had a deep-seated connection to history in the Spring and Autumn period (770-481 BCE), and were used to demonstrate that wrongdoings were met with retribution and that justice ultimately triumphed. Over time, these spirits became powerful entities and were frequently worshiped in widespread local cults.

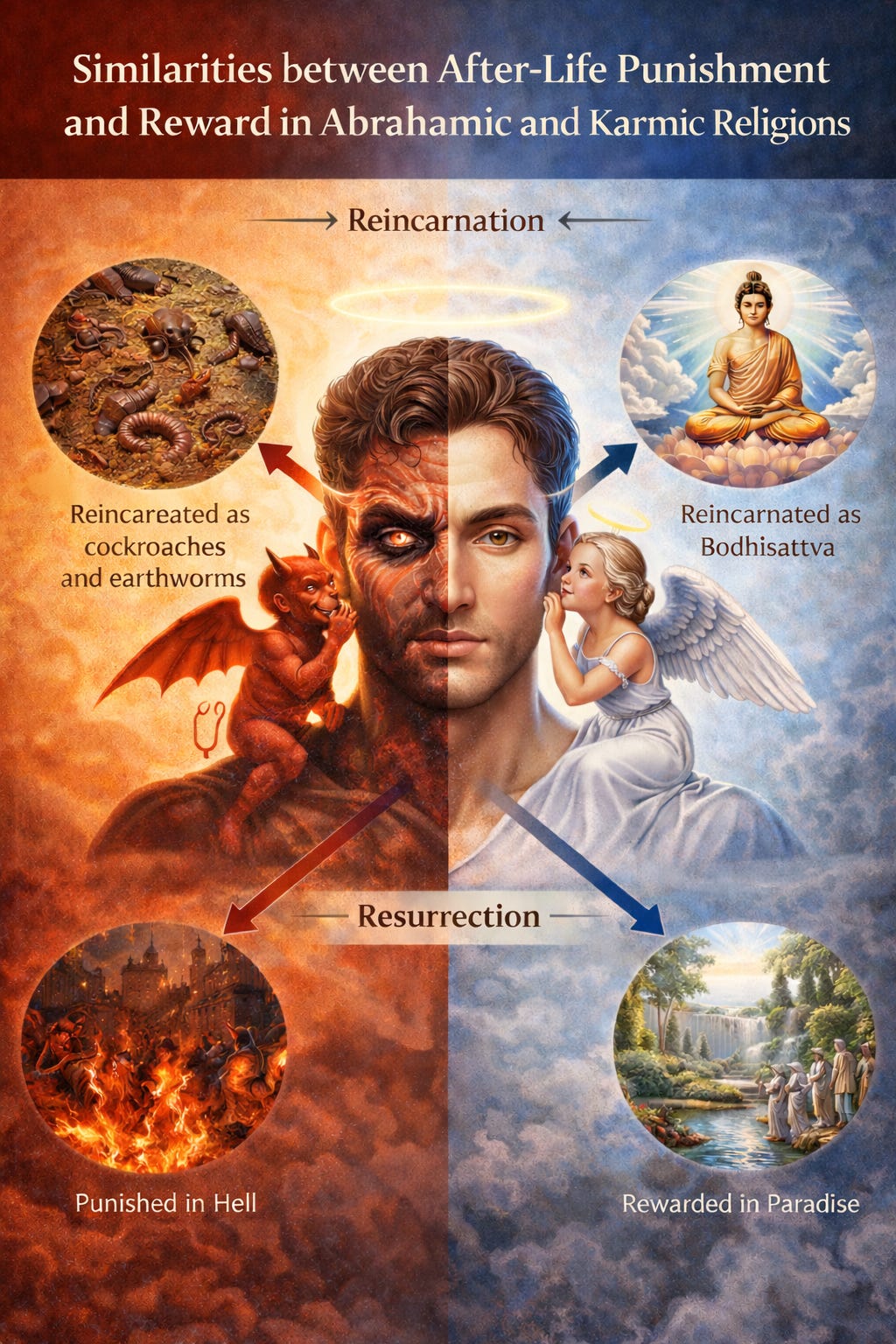

Thus, it is simply not true that religion had no role in the development of the Chinese civilization. There was no “agentic” supernatural entity. like the Abrahamic God (except in the fringe populations of Manicheans, Muslims, and Christians). But non-agentic supernatural forces, like Tian and (later) Karma, were very influential in shaping the behavior of rulers, elites, and commoners. Finally, there are lot of similarities between Abrahamic and Karmic ideas of supernatural reward and punishment.

It’s complex! And the details are very interesting.

If you enjoyed this very brief summary of how moralizing religion evolved in just one region of Earth, you will find a lot more in the two volumes of the Seshat History of Moralizing Religion, especially Volume II that provides much wonderful detail of what people believed in not just Eurasia, but also in the Americas, Africa, and Oceania.

I'm Korean. I'm not paid subscriber of Bertrand so I couldnt check the whole writings but as I check the open ones, it's just things u can know if u read eastern philosophy book or 101 class. why there was some arguements? can anyone tell me. it's the same story I learned. nthg controversial. And the time when the Sky domination transfered to Humanitarian, is when Iron come into the industry, farming, war so the structure of economics, hierarchy changed. My family and I never talked about anything about God for entire life. We r not christian. That concepts r western. If you don't have the concept you don't construct any prediction, including emotion instances(see, Lisa Feldman Barrett). As we always have been, China, Korea, national beuarecracy exam in the past, national exam to enter the university for now is the most important thing. In case of Korea, bc of our tragic history, after Japanese colonialism, Korean war, and US system introduced, not only bearacrat but plutocrat culture is mixed so now the exam and the money r the most important matters. And we never talk about life meaning. We say who think of life meaning when they live? Everyone just live hard, work hard to pay bills, feed children, care erderlys. And to live unselfish we don't talk about God. We should be unselfish bc we r "Human". We just think human should indeed be kind. I think achieving some life conditions, like job, school, marriage, money, feed myself and family is important and leading out life itself. We don't ask why those r important. Kinda empty, so including me many r exhausted, and lost to get Seoul National University, Samsung, house in Gangnam condition, kinda feel lost, wanna know what's the meaning of life, what's happiness. We suicide, don't make baby, politically divided, ...

Thanks, interesting thesis about the need for an all knowing God to overcome free riding. But “free riding” is an issue when people’s motives are narrowly focused on their self-interest. Whereas the solution that (I argue) Chinese-Confucian societies take is to expand our personal motivation to include the overall goal of living worth while lives, or being a gentleman (君子), so that our motives are no longer so narrowly focused. So here each person effectively “internalises” the free riding problem, as their goals go well beyond self-interest. Also, we can have commitments (eg to integrity, harmony) that go beyond self-goal choice. So I dispute the thesis that an omniscient God is needed.