Today the Seshat Project publishes another volume of the Seshat Histories, The Seshat History of Moralizing Religion. Volume 1: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. (Note: Volume 2: World Survey will be published August 20).

Seshat Histories is now a series, with the previous book dealing with the Axial Age. These books belong to a specific genre, “analytic narratives.” How did this come about?

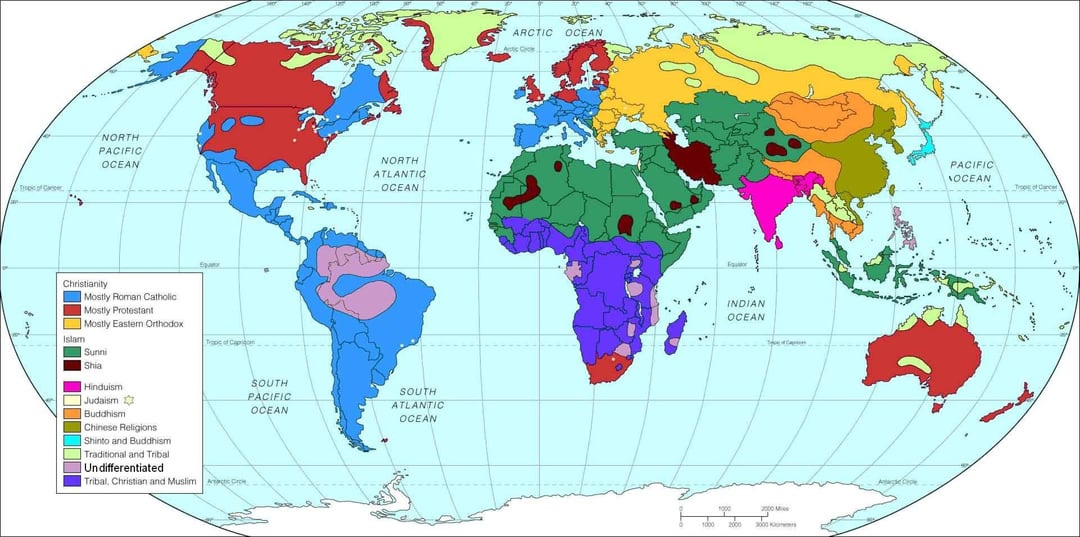

We launched Seshat in 2011 to enable us (and other researchers) to test theories about Big Questions in cultural and social evolution. One such question asks why humans have religion and, particularly, what explains the rise and spread of “World Religions,” such as Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism. By a high point in the 19th century (before the tide started receding due to forces of secularization), these religions have taken over most of the inhabited world.

Why have world religions been so evolutionary successful? An influential theory in cultural evolution has argued that belief in all-knowing, morally-concerned, punitive deities—"Big Gods”—facilitated increases in social complexity (see God Is Watching You: How the Fear of God Makes Us Human and Big Gods: How Religion Transformed Cooperation and Conflict). The argument begins with the premise that religious beliefs and behaviors originated as an evolutionary byproduct of ordinary cognitive tendencies, such as mind-body dualism. By exploiting these intuitive biases, culturally evolved beliefs in supernatural surveillance and punishment increased the ability of groups to sustain complex social organizations and successfully scale up and expand. Competition among cultural groups gradually aggregated these elements into cultural packages, in the form of organized religions. Thus, Big Gods coevolved with larger and more complex societies.

It's one thing to propose a beautiful theory, but in science theories must be tested with data. And that’s what the Seshat project did. You can read about the end result of this program on my blog archive, Big Gods and Big Societies: A Closure. In that post (and see two previous posts referenced there) I relate how our empirical results triggered a bitter controversy with the defenders of the Big Gods theory vocally objecting to our conclusions. They raised many critical points, but one relevant to today’s post was that the Seshat data was all wrong because it is simply unknowable what people believed in the past, especially before the invention of writing.

This criticism came from social psychologists, who often have a very dim idea of how history works. Of course, we don’t know everything about past societies, but it is equally wrong to say that we know nothing. This attitude is dismissive of the massive work of myriads of professional historians and other scholars of the past (e.g., religion).

But how can we connect the huge amount of qualitative knowledge historians have accumulated to quantitative data and statistical analyses? Here’s where the book published today comes in.

Analytic Narratives are formalized verbal accounts focusing on several (in our case, many) in-depth case studies. The goal of this methodology is to employ the specialized knowledge possessed by historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, and religious studies scholars, who have the understanding of the particular, for the purpose of testing theories that may apply more generally. General theory (which focuses on moralizing religion in our case) imposes structure on verbal accounts by specifying which aspects of past societies we would like to get information on. But within this framework, scholars are free to explore variability between different societies, different continents, and different eras. The aim is to reflect in the document evolving interpretations and persisting controversies, including those focusing on what is known, and what is not. Such qualitative nuance provides a much needed counterbalance to the “hard” quantitative data, which by their nature strip it away. Analytic narratives, then, are like a bridge connecting science with humanity.

The Seshat History of Moralizing Religion (especially its volume 2) is like a rich tapestry showing in detail how world religions originated in different parts of the world, and how they evolved. It’s like a broad base of the pyramid, on top of which statistical results rest. In a way, it was perhaps too early to declare “a closure” in my 2022 post. A better end point is August 20, when Volume 2 will be published.

And it’s worth acknowledging that in science we never achieve a perfect state of complete knowledge. I am sure that we will be arguing about the Big Gods theory for years ahead.

"in science we never achieve a perfect state of complete knowledge." Indeed! According to Gödel's theorem we cannot achieve perfect knowledge.

Thank you for all of your work. This has given me empirical grounding of the regenerative coherence framework I have be co-creating with AI help. I offer this as an offering in gratitude so as to help open a portal for further our collective life-coherent explorations: https://bsahely.com/2025/07/30/cliodynamics-and-regenerative-coherence-toward-a-symbolic-science-of-civilizational-pattern-chatgpt4o/